I recently paid a nostalgic visit to the East London Grand Prix circuit on the West Bank, and tried to rekindle the astonishing joys I experienced as a young boy watching the world’s greatest racing drivers in action in the early 1960s.

A rather stylish (ahem) Toyota Yaris is parked on the grid at the East London Grand Prix Circuit during my recent visit there.

The Grand Prix was a huge event, even back, then, with Norman Hickel writing on one website, East London Labyrinth, that the 1962 race attracted 90 000 spectators. I was one of them, aged about 6.

Beacon Bend is the hairpin bend in the distance, with the little hill behind being "Hill Sixty", where my dad took us to watch the Grand Prix in the early 1960s.

But how did little old East London come to host this major event? Well the website tells us that in the early 1930s, the municipality constructed a circular road on the West Bank. The then motoring editor of the Daily Dispatch, Brud Bishop, decided it would make a good race track. As any journalist would do, he wrote about it and the idea grew wings. Having been born in the UK, he used his contacts abroad to attract entries. “The entries from abroad gave the event international status and it became known as The South African Grand Prix,” writes Hickel.

The view down the main straight. Was the track narrower than most F1 circuits today?

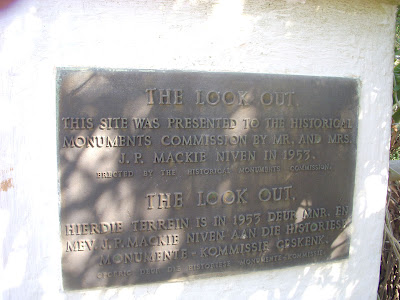

He continues: “The date set for the first South African Grand Prix was 27 December 1934. Even the old steel bridge over the Buffalo River played a part, as the bridge had just been completed but not yet officially opened.

“Mr Bishop drove to Pretoria to meet with the Minister of Railways and invited him to be the Master of Ceremonies at the Grand Prix, and officially open the bridge at the same time. Hence it was that the Honorable Mr [Oswald] Pirow officiated and presented the Barnes trophy to the winner of the race, which was attended by 42 000 spectators.

“Further South African Grands Prix took place from 1936 through to 1939, after Potter's Pass had been introduced to avoid racing through the township of West Bank. This shortened the track to 11 miles and 57 yards and it was thereupon named the Prince George Circuit. It is estimated that a crowd of 82 000 attended the 1936 race.

The East London circuit is not far from a rugged coastline. This is a view from around the West Bank Golf Course towards Cove Rock, the promontory visible in the distance - and very reminiscent of the one at Kwaaihoek in my previous posting, where the Dias cross is situated.

“Interest in motor racing was kept alive after the war by racing on the Esplanade at East London, as the old circuit had been affected by the introduction of the new airport.

“The year 1959, however, saw the opening of the new Grand Prix circuit as we know it today, cutting through the old shooting range. It measured 2.4 miles in length.

“The 6th South African Grand Prix took place in January 1960 on the new track and drew a crowd of 50 000. The 7th took place in December 1960, while the 8th happened in December 1961 and drew 67 000 spectators.

“The 9th Grand Prix took place in December 1962 and was to be the decider for the world championship. It drew 90 000 spectators.

“The 10th Grand Prix took place in 1963 and drew a crowd of 40 000, while the 11th in January 1965 drew 50 000 spectators.

“The 12th and last Grand Prix took place January 1966. It thereupon moved to Kyalami in 1967.”

I am indebted to the website, allf1.info, for this map of the East London circuit. Notice the wonderful simplicity of the track. To my mind it has the ideal mix of long and short straights, tight and gentle corners. If anyone's offended by the old SA flag, they should check out the official F1 website, where the nationality of drivers is denoted by their country's flag at the time.

Our thanks to Mr Hickel for that info. But who was involved in these races and were they official Formula One events? Well another site, Grandprix.com, reveals that “the first modern South African GP took place [in East London] in 1960 and was run to Formula Libre regulations - as racing cars were scarce - but in 1962 the South Africans won a place as the finale for the Formula 1 World Championship, and would host the event until 1966 (the final race being a non-championship one).

The distinctive moustache of Graham Hill. Note the very simple safety belt.

"Wikipedia tells us that the first Grand Prix on the new circuit was held in 1960 and that there were two races, with Stirling Moss winning one in a Porsche, and Paul Frere the other in a Cooper-Climax.

The 1961 event was won by Jim Clark in a Lotus Climax. Then came the first official F1 Grand Prix, which took place in East London on December 29, 1962, and was attended by nearly 100 000 people. A huge event, in other words.

Hill was famous for his crash helmet with white lines painted on it. His son, Damon, would replicate these on his helmet.

My dad used to always head for what we knew as “Hill 60”. This was probably an ordnance survey description of a small hillock overlooking Beacon Bend, on the far west end of the circuit.

It commanded views of cars coming out of The Esses on our right, negotiating the hairpin bend and then screaming off down the main straight, past the pits on the right and under Dunlop Bridge, which for us kids was an amazing thing. Shaped like half a tyre, it was a footbridge spanning the main straight. (Check out the layout of the circuit, courtesy of a website, allf1.info.)

Anyway, from there the cars would become long, flat shapes as they moved down the far straight and around the gentle Rifle Bend. At Cocabana Corner, another hairpin bend, they’d slow right down before careening back up the Beach Straight and then negotiating The Esses and the Back Straight. It was a miasma of colour, noise and that distinctive smell of high-octane fuel.

So who won that first official SA Grand Prix? Well, the official F1 website tells us it was Graham Hill in a BRM. But Jim Clark would be back on December 28, 1963, to win again in his Lotus. For some reason there was no F1 race in SA in 1964, but the 1965 season kicked off in East London on New Year’s Day, with Clark again victorious. It was a year when he would win six of the 10 races.

Legend. Jim Clark was a hero among us kids growing up in the early 1960s. Tragically, he was killed in a Formula Two racing accident at Hokkenheim in 1968. Wikipedia tells us that at the time he had won more Grand Prix races than any other driver (25) and also had more pole positions (33). From Scotland, he won two world championships, in 1963 and 1965. He also won the Indianapolis 500 in 1965.

The 1966 East London race was again unofficial and was won by Mike Spence, also of Britain, in a Lotus-Climax. That was the year the likes of Jack Brabham in a Brabham, John Surtees in a Cooper-Maserati and also a Ferrari (how did that happen?), along with Jackie Stewart in a BRM, were the main winners. Brabham won four of the nine races.

From 1967, sadly, the race moved to Johannesburg’s Kayalami circuit, with their inaugural event happening on January 2 of that year.

Jim Clark's Lotus, here actually being driven by Martin Brundle. As kids we would race various Dinky cars along our neighbour's lengthy driveway. We'd tie a length of string through the gap for the front axle and pull them along. At one stage the event got so big, the local service station, Els's, donated a metre-long replica of a Ferrari, the one with the side vents, as a prize. Thanks to Google, I discover this was a "Sharknose" and was driven back in 1961 by German driver Wolfgang von Trips (what a name, and his full name is about three times that length!).