The dreaded registered letter arrived. A three-month "border camp" with the Kaffrarian Rifles beckoned from, as I recall, September till November, 1983. As a full-time employee of the official opposition PFP, I tried to get out of it on the basis that I was needed in the campaign against the new Tricameral Parliament, which was to be tested in a referendum on November 2. I was even "interviewed" by the commanding officer and sergeant-major. I remember the detailed maps in that office, all around the walls, of the "operational area". That, and the danger pay they would earn, was all that really mattered to these okes. My application for exemption was submitted, but by the time I was due to leave, having spent a week or two in uniform doing training in and around East London, nothing had been heard. During those first weeks, while still sleeping at home with my new wife, I even tried to hand back my rifle. Sadly, I was told I could not and that if I lost it I would be charged. Anyway, eventually I found myself on a "Flossie" heading north-west.

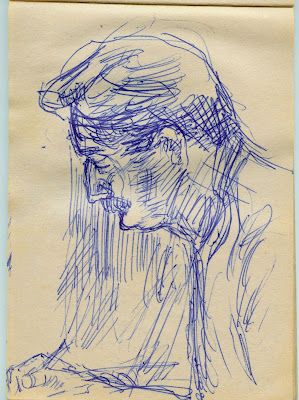

We landed at some god-forsaken spot in September where it was as hot as hell already. From there we were transported by road to, I think, Oshivelo, or suchlike, where we did a couple of weeks' more training. This was one of the corporals, his ears muffled, during some shooting range activity. I remember never actually firing a shot with that rifle - which was great, as it meant the dreaded barrel never got dirty. All the time I was sending imploring letters to the OC requesting that I be placed in a non-combatant role.

Again, as with basics back in 1979, I was drawing on the tiny, lined pages of an army-issue notebook. On the back of the above drawing were these notes from our training.

An almost charicature of another NCO during those tedious training days.

A sobering message. We were heading north, to the border of SWA and Angola, and the big fear was of our vehicles hitting mines. Here are some pointers.

The cattle in Ovamboland were very different to what I was used to, so I drew them often.

The reality. We arrived finally at the Concor base, which was apparently not far from the Ruacana water scheme. This seems to be a drawing from inside the base of an elevated guard house.

The juxtaposition of this drawing of Ovambo cattle and, inverted, notes on patrol formations, seems apposite.

There were a lot of sign boards about, extolling the virtues of the SADF and SWA's Koevoet police counter-insurgency outfit. I can't recall or make out what this one said.

Sunsets were often sublime in the semi-desert.

This is an almost archetypal image of an SA soldier, complete with snor and bush hat.

Not far from the Concor base was a rural village, which could be seen from the ramparts.

One of the ways I whiled away some time was in designing chess sets. Many of the okes also spent time carving ornaments from some or other hard seeds, having noticed that the locals were often bedecked in beautifully decorated white bangles (from plastic?) and necklaces.

I got my way as far as bailing out of active military duties is concerned. I was put into the HQ company while most of the okes walked these long patrols. I wanted nothing to do with this, so was pretty relieved when I was placed with the local "dominee" as his assistant, despite my conspicuous lack of any real Christian involvement. Anyway, part of that "winning the hearts and minds" philosophy I had been steeped in during my time at 1 Intelligence Unit during basics, was being continued here. We were given the task of helping the people of the village clean up the place. I was made to do some drawings as explanations to the leaders of the village regarding what was to be done. The above page contains a list of our objectives, interspersed with other writings.

Again, given my lack of paper, I have written around my preparatory sketches for those posters, which I recall having to do in about triplicate, so they could be passed around among the people.

I quite enjoy these chess pieces lying on their sides. At the top, too, is a quick sketch of some oke, while below in pencil is another preparatory drawing on creating toilets.

Another toilet sketch, juxtaposed with another elaborate chess set design.

Was it a buffel or a ratel? I think these mine-protected vehicles, deliberately set up high, with a V-shaped base to the troop-carrying section at the back, were buffels.

No woman, no cry. Hardly. In the absence of any female contact, the old mind did tend to wander. I did these drawings based on a sculpture I made at art school in about 1977, from silver oak, which unfortunately was stolen out of the art school.

I even got to waxing lyrical in this bit of free verse about the scenery.

Ah, and then back to that lady stretching her lithe form.

Who was he? No idea. Just another soldaat trapped with me on the border.

Once part of the dominee's office, I must have acquired some pencil crayons, which I used to embellish this sketch that, in a sense, really has a classic military feel to it.

Another project I took on was plans for a book of my army drawings, much like this blog. The best title I came up with was "The Army In Line", which is where I got the blog title from. When I got back to "The States", as they called SA, I even submitted my proposal to numerous publishers, with no success. It was not a popular issue.

SA's presence in northern Namibia was not all bad, as this canal attests. It apparently carried water from Ruacana across Ovamboland, bringing water to the people, not to mention us, as it ran right past our base. We would have to take a bucket and fill it from the canal then lug it to the toilet before doing our business.

There was a stark beauty to those northern Namibian sunsets.

More tents and a tall watch tower, clear proof that this was a military installation, though I can't recall precisely where the tower stood. We slept in tents, but the ablution facilities were permanent, and there was even a wood-fired geyser for hot water.

One of my colleagues apparently sewing a button on a shirt. I bet his wife didn't know he could sew.

The ubiquitous Ovambo cattle, with there long, curved horns.

Equally indispensable to the locals were their donkeys.

A goat, possibly one of those from the village which used to wander over the earth ramparts and come and eat the sweet leaves on the young trees we had in the base and which we had to water each morning.

They even had an aviary in the base, in which this poor love bird was a captive.

A herd of cattle. You could set your watch to the rural heartbeat, as the herd boys set off with their animals in the morning then returned at sunset.

A view down one of the graded earth walls of the base, towards a corner guard post, which was lined with sandbags, had a corrugated iron roof and housed a machine gun. It was from this point that I saw a small bit of "action". Once I was there as an assault helicopter hovered over the village and someone fired shots down into the area. I've no idea why, but it happened. Then, on another occasion, a Koevoet ratel (if that's the name for those troop carriers lined with thick little windows) arrived. Mostly, these gung-ho okes travelled sitting on top of the thing. Armed to the teeth, they were both black and white. Anyway, on one occasion I was the only guard at the gate and they left me with this captured supposed Swapo oke. He was blindfolded and his arms were tied behind his back. I was told to guard him until they returned after speaking to our OC. There I was, an arch pacifist, with this poor guy who may, today, if he survived, be part of the Namibian government.

This is another view, from that sentry post, of the dirt tracks towards the village. It has an uncannily medieval quality to it.

Sunset boulevard. Not quite, but this seems to be the sun setting over the bleak landscape.

Stand to. Each morning we had to get up before sunrise and head for bunkers all around the base. This was apparently when attacks were most likely. There seem to have been some tents nearby, possibly our medical tents used for "treating" people from the village. I quite like the silhouette effect.

A few of us regularly visited the village in pursuit of the cleaning-up operations, which were quite successful. One aspect that failed was to dig a furrow from a cesspit next to the only communal tap, where this fellow wallowed, to the main dam, a few hundred metres away. The ground was as hard as iron and even a pick axe had little effect on it.

Feeling the yoke. Another Ovambo head of cattle.

This oke was in my tent. He was a medic and his nickname, naturally, was "Doc". Here he writes a letter home.

A double take. I can't recall this oke, but I seemed to redo him midway.

A couple of local women seated under trees at that village.

One of the hallmarks of these people was their creativity. Not only did they wear lovely home-made jewellery, they also wove wonderful baskets.

But the place was pretty filthy, and this old pig revelled in it.

Had I the interest in birds I have today, I might even know what this one was.

Another of my tent mates. This was a young East London oke whose name escapes.

But, of course, the mind did wander, and to what more graceful form than that of a dancer?

I have to concede I put my dancers through increasingly enticing poses...

We had met black SWA soldier back at 1 Intelligence Unit in Kimberley, but this guy seemed to be present at that base on the border - someone who, the Swapo people would aver, had sold out to the occupation army. It was a complex war which lasted more than two decades, as SA acted as a proxy for the US in a nasty little corner of the Cold War.

Another day, another beast. I loved the lines, especially through those horns.

Another focus on the horns.

I'm not sure where these buildings were, but they too seem stark and bleak.

The bane of my time in that border base, this large oke was on the bed next to me in that six or eight-sleeper tent. He would lie, like this, and snor his heart away. I often left the tent and slept in a half-covered place where religious ceremonies were held. Still I could hear him.

That same large oke, doing what he did best: sleep. Beside the drawing, some more of my scrawlings.

He even slept with his glasses on. I can't recall what exactly he did, though.

Seated, in his vest, he was not the pretties sight, but an artist's dream.

Was this him writing home, or another slightly thinner oke? The latter, I suspect.

On one occasion I found myself in that medical tent where they handed out headache tablets and the like to the locals. I sketched one medic applying local anaesthetic - dozens of jabs with a needle - to this old guy who had almost hacked his thumb off.

I was told about three weeks before the end of that three-month camp that my application for exemption had been approved and that if I went back home now, the time I had done wouldn't count. I decided to hang in there. We were also sent our postal ballots for the referendum. I think they arrived after the event was over, but now feel they are of some historic interest.

Then, finally, it was time to leave. This plane was parked, I suspect, at Grootfontein, a large military base further south.

These choppers were also spotted there, a sign that SA was involved heavily, and expensively, in a protracted war.

No better moment. I did this sketch of soldiers climbing on board a Flossie, or Hercules, trooop-carrying plane probably while lining up to do the same.

The okes are strapped in inside the fuselage and it's chocks away and let's get the hell outa here. Actually, I can't recall if I did this on the way to Namibia or back. I'd say on the way back, though because I was hardly in a mood to draw anything on the way there. But judging by the glum look on the okes' faces, maybe not. At one point on the trip, as we flew over Queenstown with its Paris-like layout, I remember alerting the oke next to me to the dial of my watch. Watch my watch, I said. At that point all the numbers on the digital face were ones. It was 11.11am and 11 seconds on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1983, and I had completed my first - and last, though I did not know it then - border camp.

No comments:

Post a Comment